Speak Out! Save Lives.

Use these videos yourself or share with a friend.

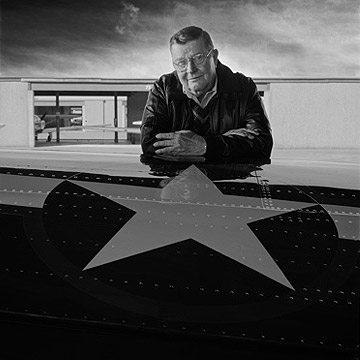

Lieutenant Colonel, U.S. Air Force 311th Air Commando Squadron

Joe Jackson enlisted in the Army Air Corps in 1941 because he wanted to be an airplane mechanic. He was made a flight engineer aboard a B-25; during a training flight, when one of the engines caught fire, it was Jackson who told the pilot what to do. Later, figuring that if he was going to have to give such advice, he might as well be a pilot himself, he went to flight school, became a fighter pilot, and spent the remainder of World War II as a gunnery instructor.

He flew 107 missions in Korea as an F-84 fighter-bomber pilot. After the war, he was one of a select group of pilots chosen to fly the U-2 “spy plane.” He was forty-five years old when he volunteered to go to Vietnam, where he flew the C-123, a light transport, as part of the 311th Air Commando Squadron.

In May 12, 1968, Lieutenant Colonel Jackson was recalled from a routine resupply mission. On the ground, he was informed that a U.S. Special Forces camp had been overrun by approximately five thousand North Vietnamese troops. Three men from the Combat Control Team who were members of an elite Air Force special operations team that had just finished overseeing the evacuation of U.S. and South Vietnamese military and their dependents were now trapped on the ground there. Another C-123 had tried to land and extract them, but it had been driven off by enemy fire. Jackson volunteered for what his radio contact at Da Nang was already calling a nightmare mission.

While orbiting over Kham Duc, Jackson saw tracers from the North Vietnamese guns along the airstrip. The camp was engulfed in flames, and ammunition dumps were exploding, littering the runway with debris. Eight American aircraft had been destroyed; a burned helicopter remained on the landing strip. As a result, the usable length of the runway was only 2,200 feet.

Jackson made his approach like a fighter pilot rather than someone flying a transport: He came down at more than five thousand feet a minute, smacked down on the pockmarked runway, jammed on the brakes, and slid to a stop. Under heavy fire, the three Combat Control men ran out of the ditch where they had been hiding. Jackson’s crew grabbed them and hauled them aboard. As the C-123 began to taxi for a quick takeoff, the enemy fired a 122 mm rocket at its nose; luckily, it broke up before hitting the plane and failed to explode. Jackson gunned the engines and took off on the shortened runway, passing through a vicious crossfire as he managed to get airborne.

President Lyndon Johnson awarded the Medal of Honor to Jackson on January 16, 1969. At the ceremony, the President had presented the Medal of Honor to a Marine from the same city in Georgia where Jackson had grown up. The President whispered to him, “There must be something in the water down there.”